IMPORTANT NOTE: I assign all credit to the referenced sources because this note is currently a regurgitation of content from various sources I have learned from, organized in a way that best makes sense to me. Eventually, I will come back and make this note fully my own after mastering the content.

Control theory can be daunting approach. However, if its presented in the right way it can be a lot more palatable, intuitive, and fun! In this new set of interconnected notes I hope to elucidate the magic of control theory for myself and others.

Preliminaries

TODO: introduce the contextualizing pieces

The Four Different Problems

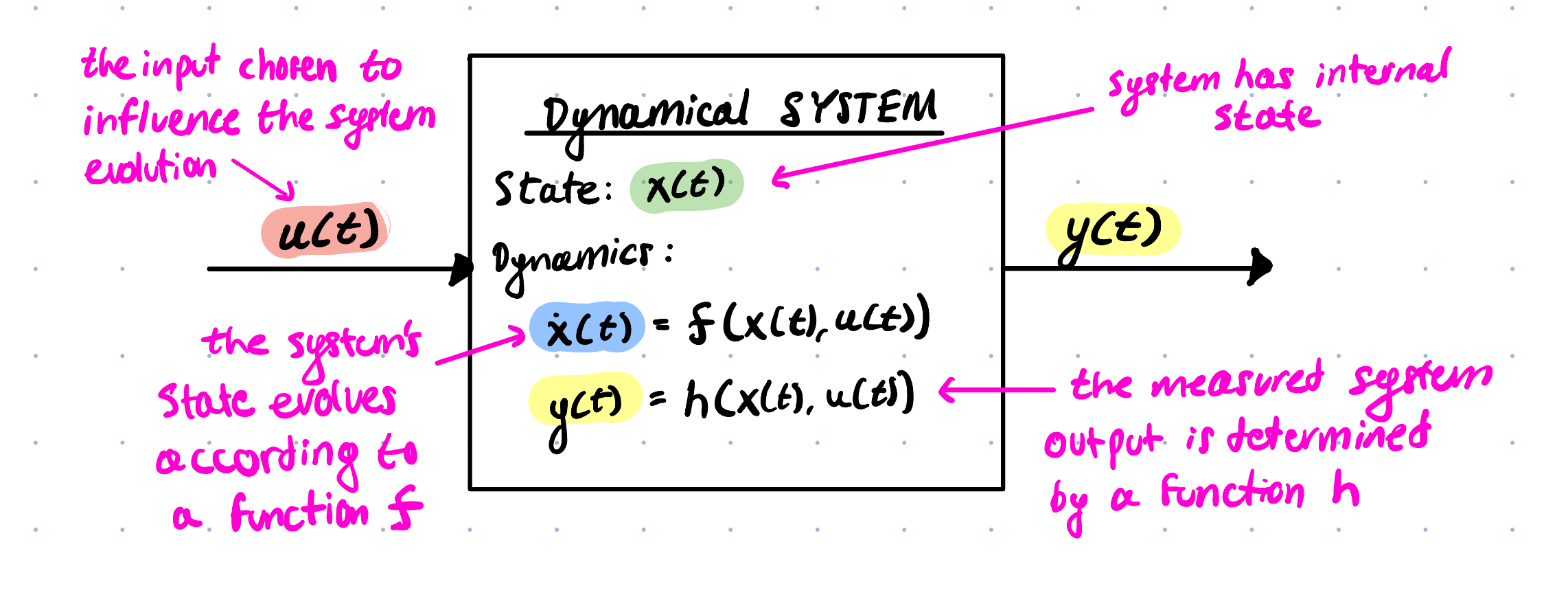

The following is a model that is useful to start looking at what control theory can offer us / help us solve:

In case it wasn’t clear in the diagram:

- $u(t)$ is our (control) input signal chosen to influence our system’s evolution.

Whichever part of the system we don’t know defines the problem we are trying to solve.

-

If we have access to the input $u(t)$ and the output $y(t)$, then our goal is to build a model of the system in the form:

\[\dot{x}(t) = f(x(t), u(t)) \;\;\; \text{and} \;\;\; y(t) = h(x(t), u(t))\]This is called the system identification problem — estimating the structure and parameters of the system’s dynamics from observed data.

-

If we have the input $u(t)$ and a known system model, our goal is to predict how the system evolves over time, i.e., compute future values of $x(t)$ and $y(t)$. This is the simulation problem.

-

If we have a known system model and observe the output $y(t)$, we aim to compute the input $u(t)$ that drives the system state $x(t)$ and output $y(t)$ toward desired behavior (e.g., tracking a reference or maintaining stability). This is the control problem.

-

If we have $u(t)$, $y(t)$, and the system model, but cannot directly observe the internal state $x(t)$, we aim to infer or estimate it, often using observers or filters. This is the estimation problem.

Borrowed this big picture approach from Brian Douglas' book and modified it slightly so all credit should assigned to him! [1]

For the keen observer, you will notice that there are many other nuanced ways to look at this model and many other questions that arise. Here are is a non-exhaustive list of some of the questions you might be asking yourself:

- What if our system model is continuous, discrete time, or some mixture?

- Are $f$ and $h$ every really known exactly? Or are they approximate? What are the implications of this?

- What exactly is the information available at the time we compute $u(t)$?

- What if we don’t want to model $f(x, u)$ explicitly? i.e, can we control or simulate the system using data-driven techniques like machine learning (e.g., RL)?

- …

As we can see, this beautifully simple model introduced here opens the door to a rich of additional questions. As I continue improve my understanding, I plan to explore each of these questions (and others) more deeply and will try to capture the implications they have for practical system design.

[1]: Douglas, B. (2017). The fundamentals of control theory.